Last time I visited the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, my mind opened. In this small gallery I stared into the eyes of the Fayum portraits, then sat in front of Portrait of Countess Golovina, by Elisabeth Vigee le Brun – a wonderful, dynamic, unsettling portrait of a young woman.

It’s been years. So when I call in again this week, ready to go on a short holiday to artworld, I can’t figure out why I feel uneasy. The building is beautiful: it’s a small museum in south Birmingham, on the green edge of the university campus. Maybe it’s memories; I miss my mother, who took me round art galleries as a child. “Please don’t carry your backpack on your back,” says the guide, like a substitute parent.

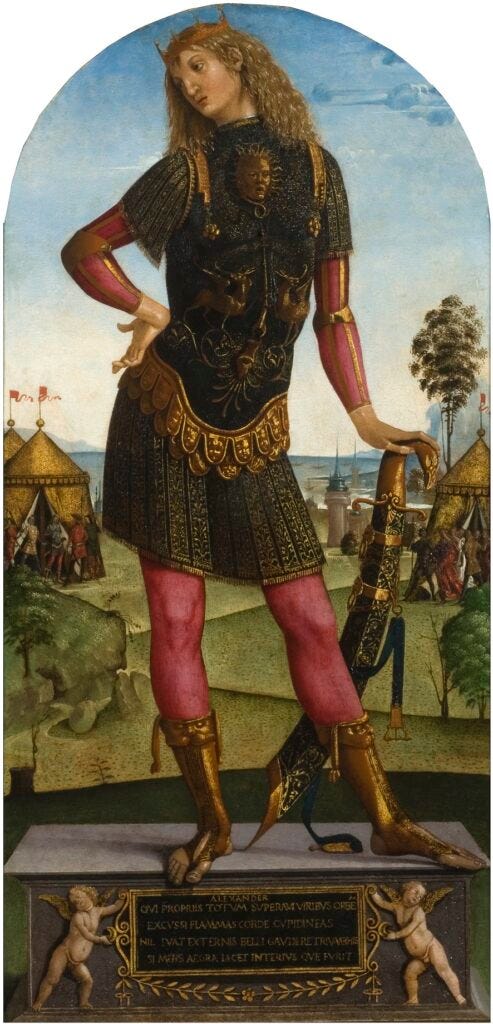

In the first room, I spend time with the portrait that inspired Othello; it’s thought to be the first painting of a Muslim created in Britain. It’s of Abd al-Wahid al-Annuri, the Moroccan ambassor to England, painted around 1600. I think about how powerful al-Annuri looks, the mixed messages sent by his stern expression. Next: Renaissance figures, Virgins, a painting of Alexander the Great – described on the placard as an LGBT icon.

In the next room, I realise why I feel uneasy: I’ve been scanning the placards as I pass by, and all the paintings I can see now are of men, by men. Of mostly white men, by white men.

Needing data for this, I make a headcount. Without walking far, I count twenty-nine works of art by men: one sculpture and twenty-eight paintings. In this room, I feel surrounded by pale male faces. The odd landscape. I pass by a portrait of a woman: she has one breast out.

I want to to give a mad laugh, run up and down the gallery. I rationalise. I’m not sure why this is hitting me today: I go to the National Gallery often, getting lost in sky-blue and gold, and NG has a miniscule number of works by women. After all, I studied History of Art, I’m a feminist, a postgraduate student. I’ve spent a lot of time looking at art – I should be used to not being in it.

But it’s one of those head-spinning moments where I see the world freshly, and this gives me a precarious feeling, as if I’m not real. Maybe all art galleries are like this? But I’ve been to exhibitions that aren’t like this. I own prints, books and postcards of art by non-men. I take out my phone and Google, ‘How many women artists in the National Gallery.’ Google automatically suggests another search: ‘How many women killed by men.’ I put the phone away.

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at art – I should be used to not being in it.

But an exhibition is open in a booth: Women in Power. I turn to it, eager to see some women’s faces. It’s a collection of historical women rulers who have appeared on coins. The exhibit is ordered around the concept of ‘Feminine Virtues.’ I’m surprised by this, because I didn’t realise women all had the same virtues. According to the text, the Virgin Mary is the ‘Perfect Woman’, the goddess Iustitia represents Justice and Mercy.

I remember the large portrait downstairs of Hattie, Lady Barber, who founded the Institute. It would be a good question — Women in Power? How did women before the 20th century get into art, making it or represented by it? Did they have to be on a coin? The founder of the Institute, or an artist’s model? The portrait artist to Marie Antoinette? The perfect woman?

I wonder if I feel like this because of Virginia Woolf: I’ve been rereading A room of one’s own this week, her seminal essay claiming that women needed space of their own and an income to create art. In one chapter, Woolf dives into the question of why “no women” created Renaissance literature, asking about the material conditions that prompted a lack of work by women: forced marriage, dark rooms, lack of freedom, constant interruptions. Woolf traces a line of women characters from the very earliest literature, all created by men. “Imaginatively [the figure of a woman] is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history.”

To get back to my little adventure in the Barber Institute. I think: well, I’m queer; I should be used to not seeing myself. I’ve had enough conversations with other queer people, about finding scraps of representation in unexpected places, how sometimes those scraps are meaningful even if unintended. Can I find any pieces here?

There’s a landscape of Primrose Hill by Frank Auerbach. The placard says that as was “customary,” Auerbach took a long time to refine the painting. That makes him sound important, gifted with infinite time. (Woolf on the division of labour: “First there are nine months before the baby is born. Then the baby is born. Then there are three or four months spent in feeding the baby. Then there are certainly five years spent in playing with the baby.”)

I start wondering if any women artists have that kind of time. It’s a good picture; this is a free gallery, a fine collection of art. I should be grateful to Frank Auerbach and the Barber Institute and stop complaining. Instead of doing that, I go and talk to another guide.

“How many works do you have by women?” I ask.

“Four.”

“Four, really?”

“It used to be two,” he explains, “but we are addressing it.”

My brother points out later that this is exponential: if they keep doubling their collection of art by women, the whole town could be overwhelmed. But never mind. I ask about acquiring more. “The problem is,” he says, “there aren’t many… You know, there really aren’t. That’s the problem.” He means women artists. I suggest that there are a lot of women modern artists the gallery could look at. “We don’t have much modern art.” He sighs. “All galleries have the same issue, up and down the country…”

I don’t mean to be rude to this guide, who seems like a kind person doing his job. I’m trying to approach this with curiosity about why it’s like this, and what’s getting done. The guide has obviously thought over this problem. He explains that women artists are scarce. I agree, up to a point. Before the mid-20th century, women artists were excluded; unable to attend art school, they often ended up creating small-scale images, landscape or botanical studies. (See this incredible collection owned by Amgueddfa Cymru, who have been working on this problem for years.) It’s a problem of undervaluation rather than absolute scarcity, a range of work that needs digging to be found and displayed.

How is this being addressed? I find out later that the Barber Institute is displaying botanical works from the V&A, including works by Mary Moser and Elizabeth Twining; The Hidden Lives of Plants is on show till November 10th. And Claudette Johnson’s Darker than Blue solo show featured there in summer 2024, with a programme of events — a fantastic, heartening step for the gallery.

I’m disappointed to have missed these; borrowing more work by women, collaborating with artists like Johnson, is a great way to address the imbalance. Still. Four? My mind keeps returning to the difficult job that the Barber Institute has – trying to redefine and expand a collection that has such an obvious gender and race gap.

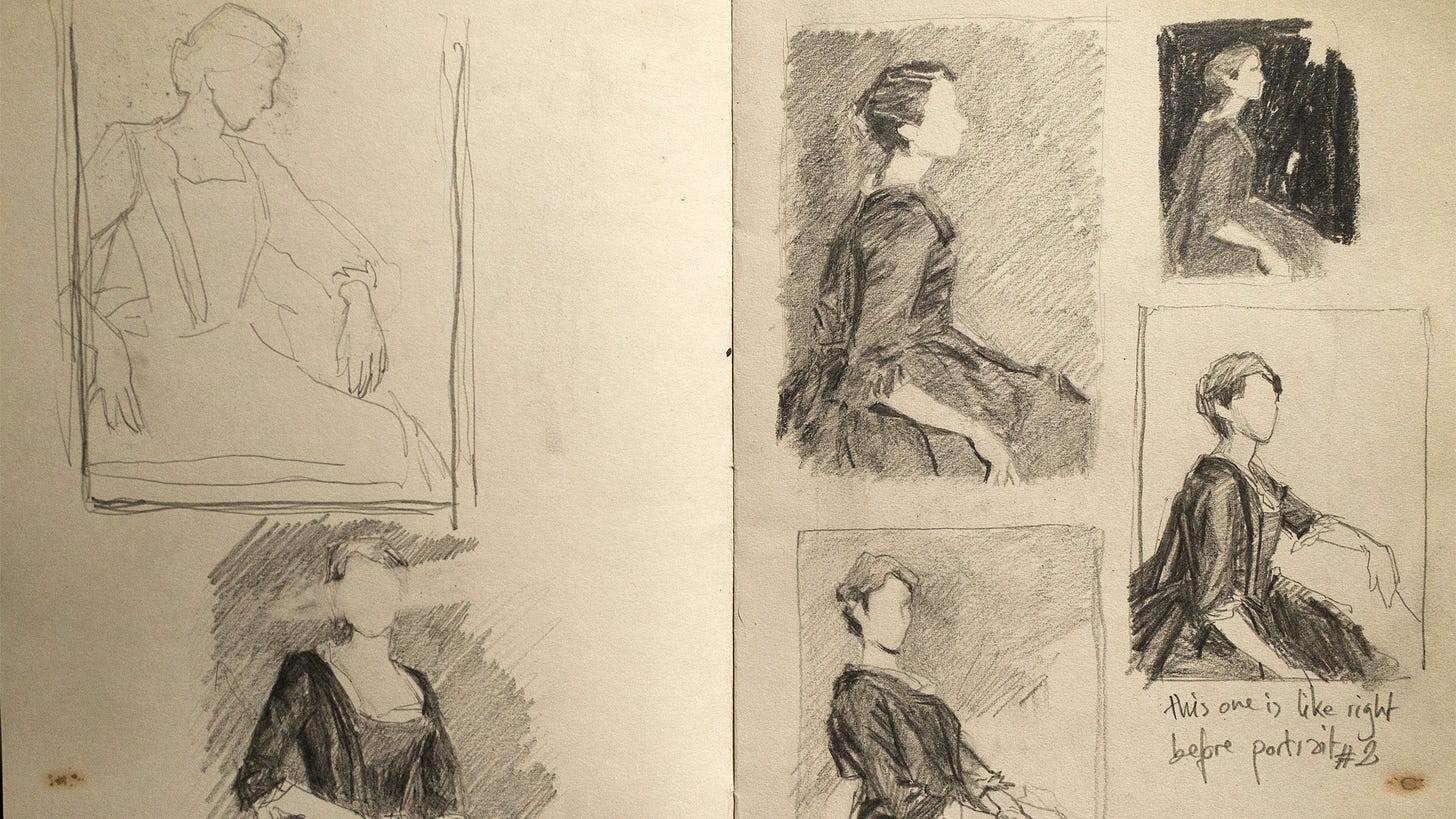

The guide asks if I’ve seen the Golovina portrait. Yes I have, I like it. The guide says that Golovina has an expression he’s never seen before in any other painting; he says this is because Golovina and the artist Vigee le Brun were “an item.”

I didn’t know this and it makes me uncomfortable. It feels like gossip, about a fine detail sewn into the painting’s fabric. In the 2019 film Portrait of a Lady on Fire, one of the final shots lingers on a portrait with a secret, in plain sight but only understood by the painter’s lover. Something too familiar to be itemised. Am I being too protective of my people? I think of my younger self – questioning, precarious – the deep connection I felt with the work, back then. No guides back then hinted that leBrun was queer…*

I would love to know what next steps the Barber Institute will take to expand its collection. Apparently Round Lemon Collective ran an intervention back in 2023 – drawing attention to the gender gap – which sounds fantastically interesting, and more power to them. I hope for more interventions, more solo shows, because on this autumn day, I looked around and couldn’t see for the gap. Women portrayed by men, women on coins, the odd exception like Countess Golovina…

“Women,” says Woolf, “have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.” If women tell the truth, “the figure in the looking-glass shrinks; his fitness for life is diminished.” Museums and galleries can organise their collections and review their story-telling, to reflect today’s concerns more fully. The representations of women in the Barber Institute mirror men’s preoccupations from hundreds of years ago to now; I’m fascinated to see how the Institute keeps adapting to reflect us today. As the guide says, they are addressing it. What about all the other galleries with four works by women?

I find the Golovina portrait. Her cloak looks less red than in my memory, her expression is vibrant, full of hope and trust, as if she truly believes the world can be better. I wonder what she’d think about the collection here, about seeing herself.

*The number of women artists’ works in the National Gallery is 27 out of 23000. According to the site, their works are in the collection because of the women artists’ “determination and talent.”

**I could find nothing to confirm if Elisabeth Vigee le Brun and Golovina were in a relationship; le Brun’s sexuality seems to be a question mark.