I went to BMAG and saw women! And Gluck

To acknowledge and seek to repair the inequalities in art, past and present.

Last month I wrote about walking into an art gallery and seeing no work by women artists. After getting a few howls of solidarity (thank you!) I dropped in on Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. BMAG has just reopened; the main site has been closed since 2020, due to renovations on the Victorian building that houses it.

It’s a splendid site — a lofty entrance hall, a staircase with mosaic tiles, and an intricate, honeycomb network of galleries. Having found out that the Barber Institute only has four works by women artists, I was on the lookout for women, not just faces but names. BMAG gave me a promising start: in the entrance hall I was greeted by a row of portrait photographs of local community workers, including a portrait of a gardener I knew growing up.

The place is looking well. It was like being welcomed by an old friend. People poured in — students, couples, families with children. Toddlers rushed round, older children asked questions. Everyone visiting looked like my neighbours. An atmosphere of mayhem, chaos and curiosity reigned. In that spirit, on the lookout for women, I decided to engage with a quick count: how many women artists?

For my data collection I stuck to the Round Room — the vibrant central gallery, which the rest of the museum revolves around. I’ve always liked that Epstein’s sculpture of Lucifer (1945) takes centre stage. Not just is it daring to focus the room on a statue of Satan, but it’s fantastic. The wings burst upwards and outwards, giving a focal point to the room. Historically, the Round Room has held a permanent exhibition focusing on 19th-century landscape paintings by men.

The One Fresh Take exhibit is an improvement. Walking around, I counted five works by women: Lubaina Himid, Fiona Rae, Joan Eardley, Bridget Riley, and Laura Knight. I’m not counting the intriguing work by Gluck, an artist who maintained gender neutrality and identified with no movements. (According to Wikipedia, when listed by an art society as Miss Gluck, Gluck resigned.) Himid’s double portrait, My Parents, Their Children (1986) was prominent and impressive, a treatment of family history regarding ancestors from different sides of the family who never met each other.

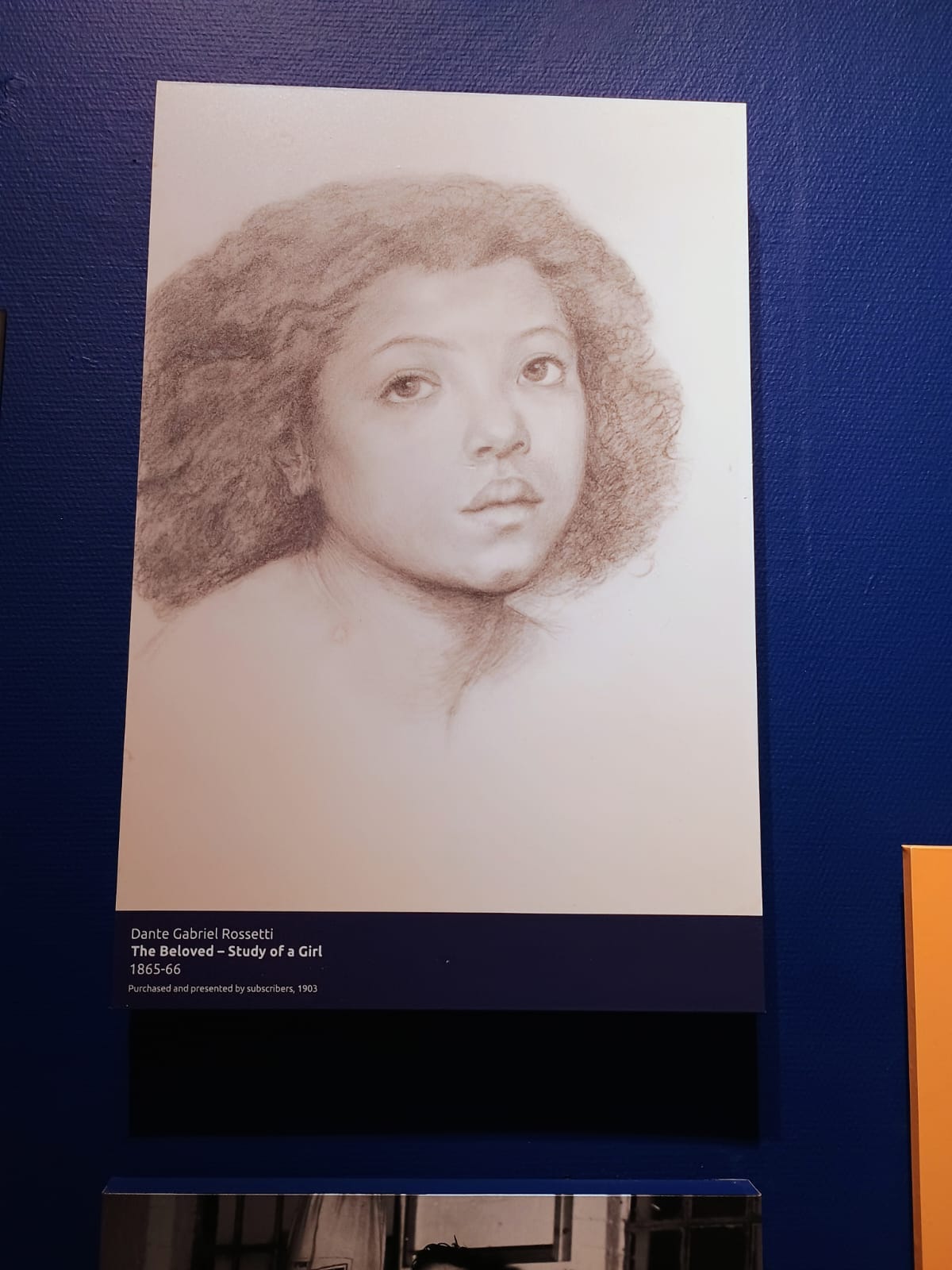

One of the challenges faced by BMAG, with its collection of mostly Victorian art, is how to adjust to the present day and the changed city. And not just that, but how to acknowledge and seek to repair the inequalities in art, past and present. A work like Rossetti’s The Beloved — Study of a Girl has resonances of injustice. We don’t know this girl’s name, but we do know that the child in the finished Beloved may have been enslaved in his life, was forced to participate in sitting for the painting, and cried throughout the sitting.

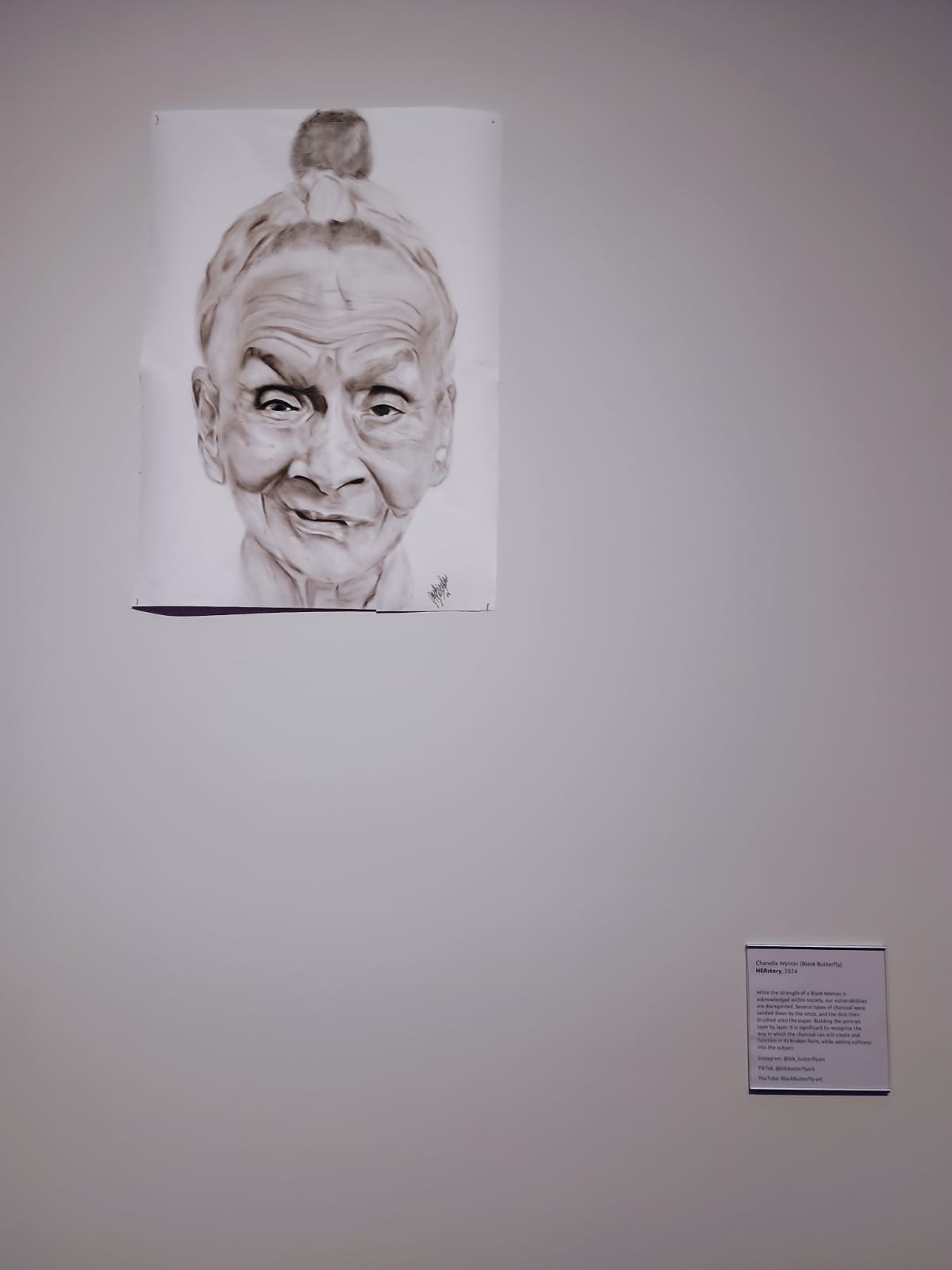

One tactic used by BMAG is to juxtapose images. The Beloved study is near a photo of Benjamin Zephaniah and one of his poems. The Deviance & Different exhibition mixes portraits by contemporary artists of colour, like Chanelle Wynter, with well known modern artists like Barbara Hepworth.

In general, I was delighted to see more Black faces and artists around the gallery, and to notice the mix of visitors pouring in. I’m cautiously optimistic that BMAG is engaging with inequality. Make no mistake, BMAG’s problem is the art world’s problem.

I spoke to a guide, who was just as thrilled as I was to see a range of faces and names on the walls. She was practically bouncing up and down, quivering with enthusiasm.

“How many women artists do you have?” I asked. The guide said, “Good question,” and phoned the curator. We both waited eagerly, but the curator couldn’t provide a number of women. I’ve since emailed BMAG with my question, but have not yet got a reply.

“We are working on it, though,” the guide said, “and our Victorian Radicals exhibition in the Gas Hall has women artists, please go and see it!” What a change from the person I spoke to at the Barber Institute, who made acquiring work by women sound like a mammoth task that was borderline impossible.

One of BMAG’s pressing challenges is to restore the full museum. The site is reopening in stages; the Gas Hall gallery, joined on to BMAG, reopened and launched a display of Pre-Raphaelite art in February. While the Gas Hall and the main galleries are now up and running, sections of the building are still unusable and in disrepair.

Thankfully, there’s been a concerted push against discussion of selling the collection off: Birmingham has already lost so much. For those families enjoying the collection, what other third spaces do they have? To take my own family, my dad grew up on a council estate in the 60s, a place where children were put outside to play all day while their parents worked at the car factory. When I tell him about the toys that kids have now, he replies, “When I was a kid we had no status symbols, because we had no status.” At the same time, one of his joys in life has always been to go to BMAG and look at the works by Edward Burne-Jones. At their best, free museums are a fabulous generator of culture, enriching every life that comes in through the doors.

Materially speaking, though, I couldn’t help wondering how many of the women artists and/or artists of colour featured are making a living from art, how these works were selected and how the artists were reimbursed. BMAG feels like a microcosm of the art world: a splendid Victorian site in partial disrepair, a collection of costly art by established names, and a selection of works by artists who may be struggling to pay the rent.

But — cautious optimism. I felt welcome. The reopening feels like a new burst of energy: a house with open doors.

I really love each time I read one of your posts - it feels intimate and warm and funny, like listening to someone's day over a beer or a tea. much-needed in my inbox!