Maker Unknown: thoughts on Victorian Radicals

I viewed an Arts and Crafts exhibition, but something was missing

The Lacemakers

“The tight weave of traditions that makes a comfortable hammock for some just as surely makes a noose that strangles others.” - Anneli Rufus, Party of One: The Loner’s Manifesto

“I’m a weaver, a master weaver.

I’ve got a loom where the best cloth’s made.” - Oliver Postgate

This year I’ve been researching my family history, creating a timeline which is almost all gaps. Go back just fifty years, and next to nothing is written down. My ancestors were not well educated people. Maybe I write too much because they didn’t know how.

I traced my great-grandmother’s last name back from mid-century London to a village called Cranfield, in Bedfordshire. To my surprise, I turned up a list of names: women living in the same cottage, their occupation listed as Lacemaker.

Bedford lace, or bobbin lace, was a delicate substance, and the method for making it was handed down from mother to daughter. Bedfordshire was one of the places where lacemaking by hand held out, after weaving was mechanised. A lacemaker needs extreme patience, a gift for nimbleness. The lacemakers worked hard to eke out a living. Daughters stayed at home to learn the trade. Boy children — including my great-grandfather — tried their luck in London, instead of staying in the village.

Actually, my mother had lacemaker qualities: she decorated every wall in our house with paint and stencils. Sea blue for the bathroom, children’s book illustrations for the bedrooms. She loved crafts so much that she even bought me a child-size loom. I dutifully wove a needle through the strings for what must have been hours. I didn’t know why I was doing it, or why I was supposed to like weaving. I have the kind of dyspraxia that confuses right and left, but nobody knew about it.

Luckily, I also have a vivid imagination, so I probably thought of medieval castles and imagined I needed to keep the winter cold away. I ended up with an uneven-looking blanket in primary colours. If there is any weaving talent left in the family, it’s keeping very quiet.

Maker Unknown

With family history in mind, I viewed the Victorian Radicals exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG). I’ve been carrying out a project where I view exhibitions and count how many works by women are on show, so I was interested to see how that played out with an exhibition about the Pre-Raphaelites and Arts and Crafts.

Not everyone has heard of these movements, but we’ve all seen William Morris notebooks and memes of Millais’ Ophelia. Actually, the iconography has soaked so far into visual culture that it’s hard to imagine stepping out of a grey Victorian day, into a museum, and seeing Medea for the first time.

I think a key challenge of this exhibition is to defamiliarise these art objects, reposition them to show how radical (or not) they were at the time. Curation is storytelling. The first painting I noticed as I walked in was Ford Madox Brown’s Work. Hung in pride of place, this incredibly complex picture is worth a long look — both realistic and improbable, it confronts the viewer with a group of intriguing ‘lowlives,’ poor people taking centre stage. To see how revolutionary this was, compare with the tiny figures in this clean, spare illustration of Blackfriars Bridge being built. Then imagine if those neat Instagram photos of London streets included portraits of homeless people and labourers right at the centre, living breathing subjects. Pre-Raphaelite painting embraced detail — frantic contrasts, an abundance of figures, maximalism!

While this was a fantastic opener, I was on the lookout for works by women. I made my way round the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood paintings and saw portraits of impressive women galore, but with few works by sisters, barring small but intriguing works by Lizzie Siddall and Emma Sandys. The first prominent artwork I stumbled on was an embroidered bedcover by Mary Jane Newill.

The Arts and Crafts Movement, led by William Morris, focused on the worth of handmade crafts over mechanical reproduction. Newill studied at the Birmingham School of Art, taught needlework and embroidery there, and was part of the Birmingham group, a loose gathering who embraced Arts and Crafts. To show the contrast between ‘manmade’ and handmade, BMAG hung Newill’s tapestry opposite a mass produced carpet, which looks disorientingly like any plastic-wrapped carpet that could be bought on the Stratford Road in Birmingham, complete with deep red roses. It’s clear to see the depth and individuality of Newill’s piece, with its richly detailed owl and swallows. I like how the piece calls for engagement and interaction — following the text of Wordsworth’s poem around the border.

From there on, the exhibition opens out and becomes more diverse. The Pre-Raphaelite section focuses mostly on well-known works by men — and, for me, it’s hard to break through that familiarity. But the Arts and Crafts section has more room to play. I learned about Newill, and other women artists at the Birmingham School of Art. There were works by William Morris’s daughter, May Morris the dressmaker: an elegant tiny pair of shoes, a child’s shift miraculously thin and more than a century old. A fascinating draw was an understated emerald day dress, trimmed with black ribbon: Maker not recorded.

‘A prison of textiles’

Studying the works by named women, I kept wondering what they wanted to say with their work, how they saw themselves. Did they see themselves as followers of, say, William Morris, or did they wish to be independent names? There are amazing oddities. Like May Bunting’s Portrait of Offlow Scattergood — a portrait of a woman artist by a woman artist. The only known piece by Bunting, the artwork deliberately portrays Mary Offlow Scattergood in a typical Elizabethan pose, with a pet, surrounded by a repeating pattern of roses — or are they Alonsoa meridionalis, a flower also known as 'Rebel'?

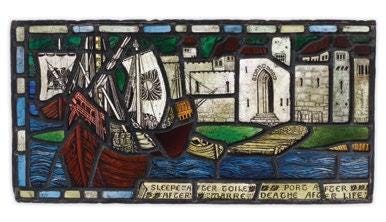

The medievalism of Newill’s ceramic piece Sleepe After Toile is interesting, imagining an idealised medieval past of sailing ships and the sanctuary of a castle. I find the disjointedness striking — a departure from Burne-Jones’s work in stained glass, which is glossy and harmonious. It’s a confident statement, but what is it saying?

I was intrigued that much of the women’s artwork looked traditional, embracing medieval and Renaissance imagery. Kate Elizabeth Bunce’s iconic Musica is straight from my childhood imaginary medieval castle. There’s a strong theme of nature imagery, especially seen in Gwendoline Kate Lewis’s purses with their cornflowers and love-in-a-mist. It was great to see women co-credited as participants in artworks, too, including Myra Bunce as a metalworker — inserting metal into the picture frames.

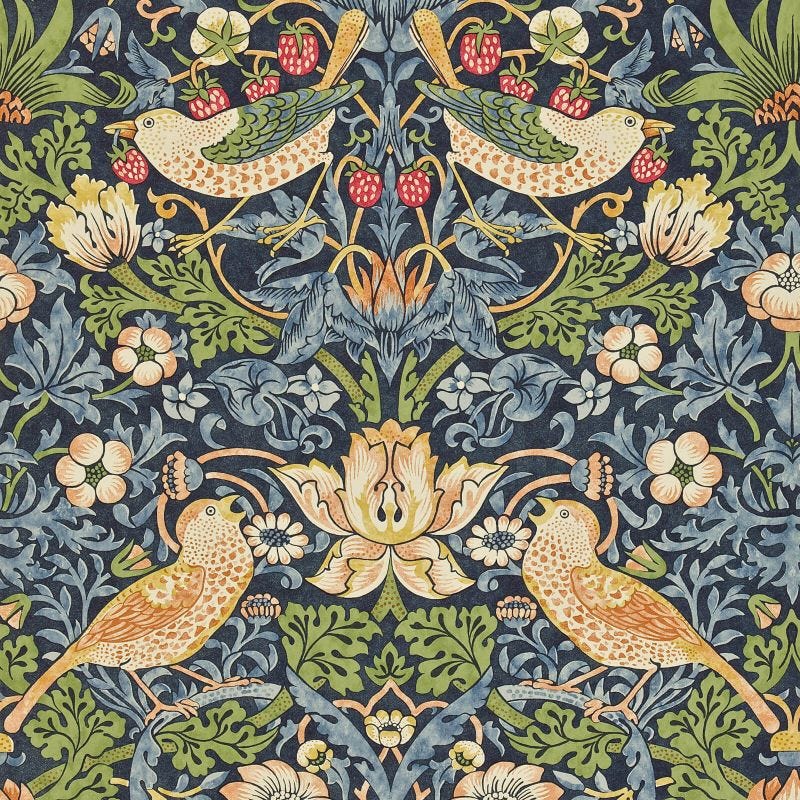

But what values were being shared in this work? This exhibition has so much content, organised in a small space, that I can’t imagine the challenge of creating an all-inclusive narrative. Still, it feels as if key pieces of the pattern are missing. Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s poem, Strawberry Thief Singing, is displayed next to the Morris pieces:

“The thrush, caught jubilant, after stealing

ripe fruit from the artist’s garden, goes to

a prison of textiles, serves a sentence

of centuries in cotton…

She will be stretched on Raj furniture

across the commonwealth, a souvenir

in chintz, her crime displayed on bedspreads.”

The website has a lovely piece by Gursimran Oberoi which addresses Morris’s connection (or lack of) to Indian labour:

“How has ‘Strawberry Thief’ come to be considered as quintessentially ‘English’ or ‘British’ when its creation is implicated in the physical, creative and economic displacement of world cultures under British and European imperialism and colonialism?”

… “As letters to family and friends evince, Morris’ experiments left his hands and forearms ‘permanently blue’. His toil mirrored the work of thousands of unnamed Indian labourers who for centuries had produced and dyed cottons and silks using the plant, Indigofera tinctoria.”

This is a great, beautiful, much needed start to unravelling the neat and beguiling embroidery of Arts and Crafts. Looking at the placards around works influenced by him, like Newill’s bedcover, I felt that the notions of Englishness sustaining Arts and Crafts and the Pre-Raphaelites were gestured to, but not addressed fully. The Pre-Raphaelites used the exotic to draw interest — like the lion skin worn by Morgan le Fay in Sandys’ painting, or Simeon Solomon’s indulgent, eroticised dark-skinned figure in Babylon hath a golden cup, or the forlorn Black child whose face and body Rossetti sketched for his work Beloved. With the exception of Solomon’s painting, these figures and motifs are satellites, revolving around and offsetting the central figure — almost always a beautiful white woman.

Meanwhile, the poem quoted on Newill’s bedspread was written in 1804 as the Industrial Revolution gathered speed. Works like Strawberry Thief and Newill’s bedspread hark back to an idealised English rural past, one that never existed but provided a rich fount of imagery to sell wallpaper for townhouses. I don’t have to go into how notions of an idealised past are key to fascism, or connect one with the other; but I notice this English past being celebrated and idealised in these works, and say “Hm.” I now have to admit a prejudice and say that I don’t enjoy William Morris patterns too much: I find them claustrophobic and static. For me, they evoke the close tangle of furniture in late Victorian rooms, the tight weave of obligations, the need to perform good manners, the pressure to agree that the past was always better. Or is that just me?

I would love to know what drove artists like Newill to embrace Arts and Crafts: was it a desire to explore the possibilities of overlooked media? Nostalgia for the Middle Ages, fed by a desire to return to an imaginary brighter, cleaner past full of powerful and desired queens? At the same time, their positionality is so interesting: recognised for their crafts, in an era when most craft by women was made up of useful piecework, handstitched or mass produced in factories. Maker Unknown.

Hashmi’s poem speaks of a “prison of textiles” — relevant now as ever, when the textile industry pays so little to its key workers, and women artists are still undervalued. I’m happy to see a greater inclusion of women, and delighted to see this poem featured on the wall to guide the narrative; yet the poem’s challenges are not all addressed. Let’s critique Morris more! The poem challenges notions of prettiness and artistic unity: the thrush’s shape is repeated over and over until it loses meaning. The weave of tradition comforts some and strangles others…

Victorian Radicals is on until at least Christmas 2024.

Note: BMAG’s curator has contacted me about the number of women featured in their Round Room and other exhibits. I was happy about BMAG’s openness and willingness to take part in the discussion, and hope to share figures next time!

Works by women count: 18.

I really love your writing, and each time you make me think deeply about the questions you raise.